Following Blount’s death, the Steamtown Foundation trustees named Edgar Mead director of the foundation in October 1967. Mead’s first action was to ensure the future of Steamtown at Riverside. In his lifetime, Blount had funded much of Steamtown’s development himself in addition to transferring his private collections to the effort. But Nelson certainly did not expect to perish so soon in the way that he had, and as reported by Fred Richardson, there was no residual money for Steamtown in his existing will.

Mead later recalled the financial struggles that emerged in the wake of the tragedy. “All roads led to Nelson Blount on this project; he had the momentum, resources, and he had the target of what he wanted to do with this so it could not possibly happen at a worse time, but we picked it up as best we could. At the first meeting when I became chairman we felt that, A: Since there was no money we had to spend most of our time fundraising, and B: the collection simply could not be left outdoors to rot in the severe winters of Vermont. So, what money we were able to raise we put into sheds and, during my tenure at Steamtown, we had been ableto cover about half the collection”.

The trustees intended to carry out Nelson’s vision, which had only finally begun to move towards reality when he passed. Mead appointed Reynolds J. Anoe as curator of the collection. Numbers-wise, things were looking bright for Steamtown. 1967 attendance nhad risen to as much as 20% higher than 1966, despite markedly poor weather throughout the season. Visitors to Steamtown USA were 48,326, as opposed to 40,855 in 1966. The NEPCO Farm property, which had previously been purchased by the Green Mountain Railroad, was given to the Steamtown Foundation.

The Monadnock, Steamtown & Northern Amusement Corporation ceased operations on December 31, 1967. Just prior to Nelson’s death, passenger operations had become the responsibility of the Green Mountain Railroad and would remain so until August 1970. The MS&N, no longer operating, now simply owned real estate and rolling stock. Ruth Blount, who had also served as an incorporator of the MS&N, inherited control of the corporation, its assets, and its real estate as decreed by Nelson’s last will and testament. Along with Fred Richardson, she had every intention of transferring the MS&N’s assets over to the Steamtown Foundation but desired to wait until the Foundation was on sturdier ground. The three organizations which Blount had led the way in creating — the MS&N, the Green Mountain, and Steamtown USA — were all heading down different paths.

Steamtown in the 1970s

And so the Steamtown Foundation forged ahead into the 1970s, but the Vermont Environmental Protection Agency sought to enact clean air regulations which would force the costly conversion of the steam locomotives to burn propane. It was unlikely that the for-profit Green Mountain Railroad would be able to advocate for an exemption, but the non-profit Steamtown Foundation had a chance and prevailed with a permanent variance. On August 28, 1971, the Green Mountain Railroad and the Steamtown Foundation went their separate ways officially when steam operations reverted solely to the latter. 2-6-0 #89 was sold to the Strasburg Railroad of Pennsylvania in 1972, and 4-6-2s #1246 and #1293 were sold to Steamtown; the Green Mountain was officially out of the steam passenger business. There was to be some tension between the two groups in the days ahead, specifically involving shared properties and maintenance to the tracks upon which they both operated for different purposes. All in all, the two ended up coexisting well.

Over the next twelve years, Steamtown USA remained a popular yet troubled attraction. Its steam excursions and famous Railfans Weekends were well-frequented and photography from this period abounds. Yet the high visitor levels anticipated by Blount and the Town of Rockingham were never realized; in Steamtown USA’s best year, 1973, there were 65,000 paid admissions — far fewer than other New England tourist railroads with smaller collections in better locations. Nelson Blount’s Steamtown USA was never realized; the grand roundhouse, museum buildings, and replica Yankee village never saw construction. Only Phase I, with its landscaping, construction of storage tracks, and installation of a turntable and storage buildings, saw completion.

Without Nelson’s support and dedication at levels both financial and personal, his dreams could not be realized. “What we used to do was take advantage of our hundred-day season and create as much money as we could to survive the winter”, Edgar Mead later said in 1994. There was absolutely no money from the state or from the town. The town, begrudgingly, gave us tax exemption because the town fathers knew that we did bring a lot of people to town to sleep in the motels and buy gasoline. Steamtown, we thought, was certainly a great benefit to Bellows Falls. At the same time, we thought that we really had to look elsewhere.”

Vermont, it turned out, had been a welcome escape for Nelson from his troubles in New Hampshire, but the Green Mountain State was far from a perfect fit. It was just not a suitable environment for the type of high-volume tourist attraction which Steamtown needed to be, especially with the high maintenance and upkeep expenses demanded from a steam railroad operation. Vermont had strict advertising regulations which would not allow for signs or billboards, and though there were many friends in local and state government, these issues could not be resolved. Additionally, harsh winters had led to accelerated deterioration of the collection and even the partial collapse of the engine shed later in 1981 which damaged several locomotives.

Mead and his successors set about accelerating the search for a new home which had reignited in the 1970s. For a time, Florida, with the offer of twelve month operating seasons, once again seemed a welcoming choice. In the 1970s Mead traveled there to review architectural plans. Mead also looked into

Union Station in Washington, DC, prior to the start of Amtrak on May 1, 1971. Mead served as director until his resignation in 1973.

The Robert Barbera Years

Mead was replaced by Robert A. Barbera, Sr., whose father, former Lackawanna engineer Andy Barbera, worked as an engineer at Steamtown. Robert Barbera had a drastically different outlook on Steamtown, coming at it from a more analytical and economic perspective. This certainly owed to his past in science and business. “I am not one of these avid railfans, quite to the contrary, I viewed it as a business first and second”. Barbera’s outlook was drastically different to Nelson Blount’s original intentions but did help the foundation survive economically throughout the 1970s. In 1972 Robert Barbera had begun an extensive advertising campaign, which had impressed the board of trustees. This was a major contributor to his being awarded Executive Director. TV ads also proved very effective in building the business, assisting in raising attendance from 200 attendees on weekdays and 400 on weekends to 600 and 1000, respectively.

Soon after Barbera’s appointment Fred Bailey proposed a Railfans Weekend, yet Barbera was skeptical. “Bob Barbera really wasn’t a railfan per se, and I didn’t know what his reaction was going to be to that suggestion, because he looked at things from a dollar and cents point of view”. Barbera was not keen on the idea, stating “I don’t think railfans are going to pay for an event. I don’t think Steamtown should spend its money doing photo run-bys for fans that are not going to pay for it.” Thankfully, Barbera gave the idea a chance, and Steamtown’s Railfan Weekends became very successful, although at times, expensive. Meanwhile, Barbera proposed the prospect of moving the museum to Kingston, New York, with operations on the former Ulster & Delaware line, but this proposition also died due in part to local opposition in New York.

Vermont Bicentennial Steam Expedition

1976 was a big year for the country and proved just as monumental for Steamtown. To commemorate the United States Bicentennial and also the bicentennial of the Vermont Republic in 1977, the state of Vermont proposed a two-year event with special steam-powered trains operating around the state. Originally the plan had been for three trains operating simultaneously, but the cost estimates soon made it clear that only one train was all that was affordable. The state had initially seen Steamtown’s estimate as somewhat of a rip-off and processed to field other offers, only to discover that Steamtown’s was indeed the best avenue! This delayed the green light until March 1976.

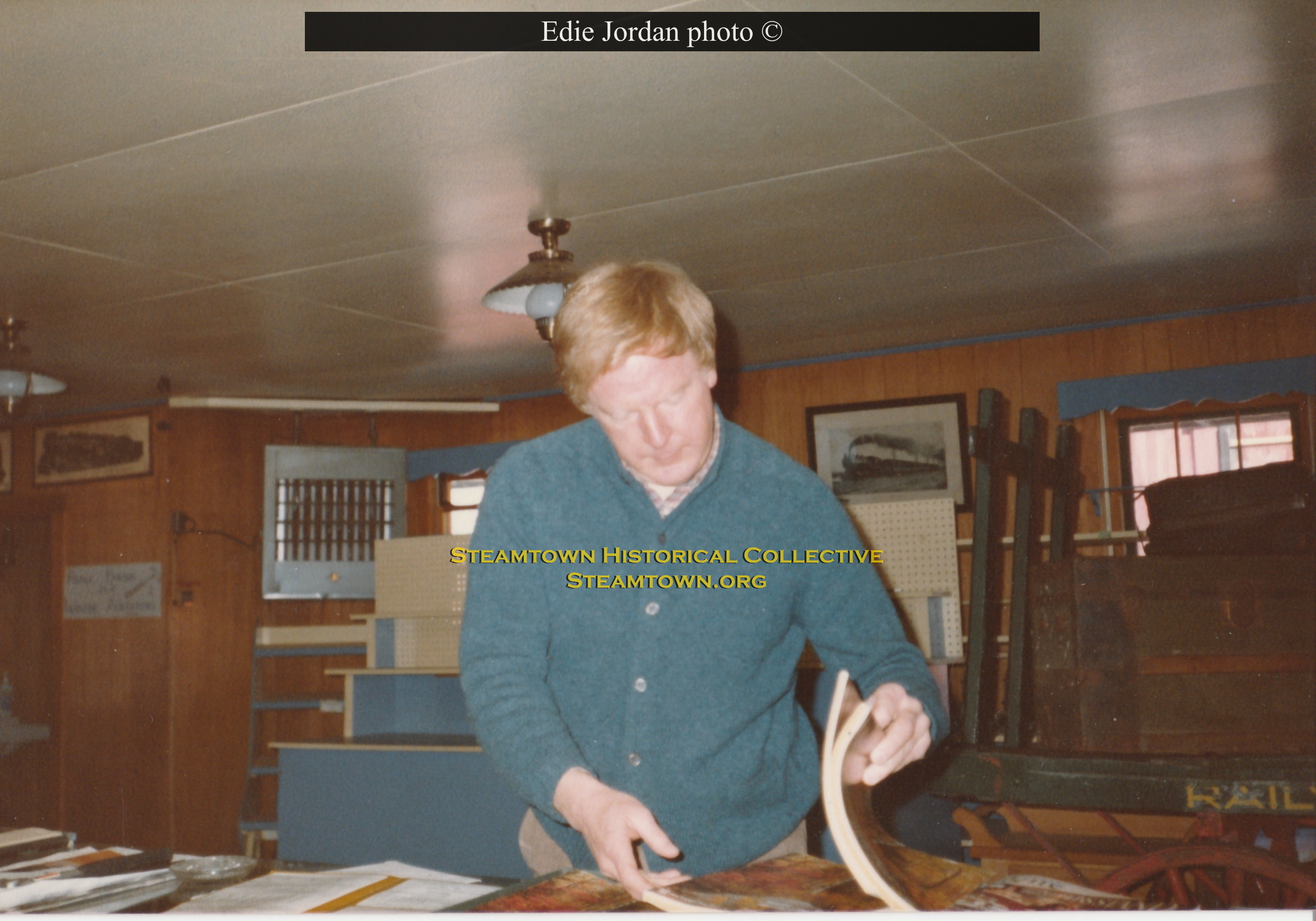

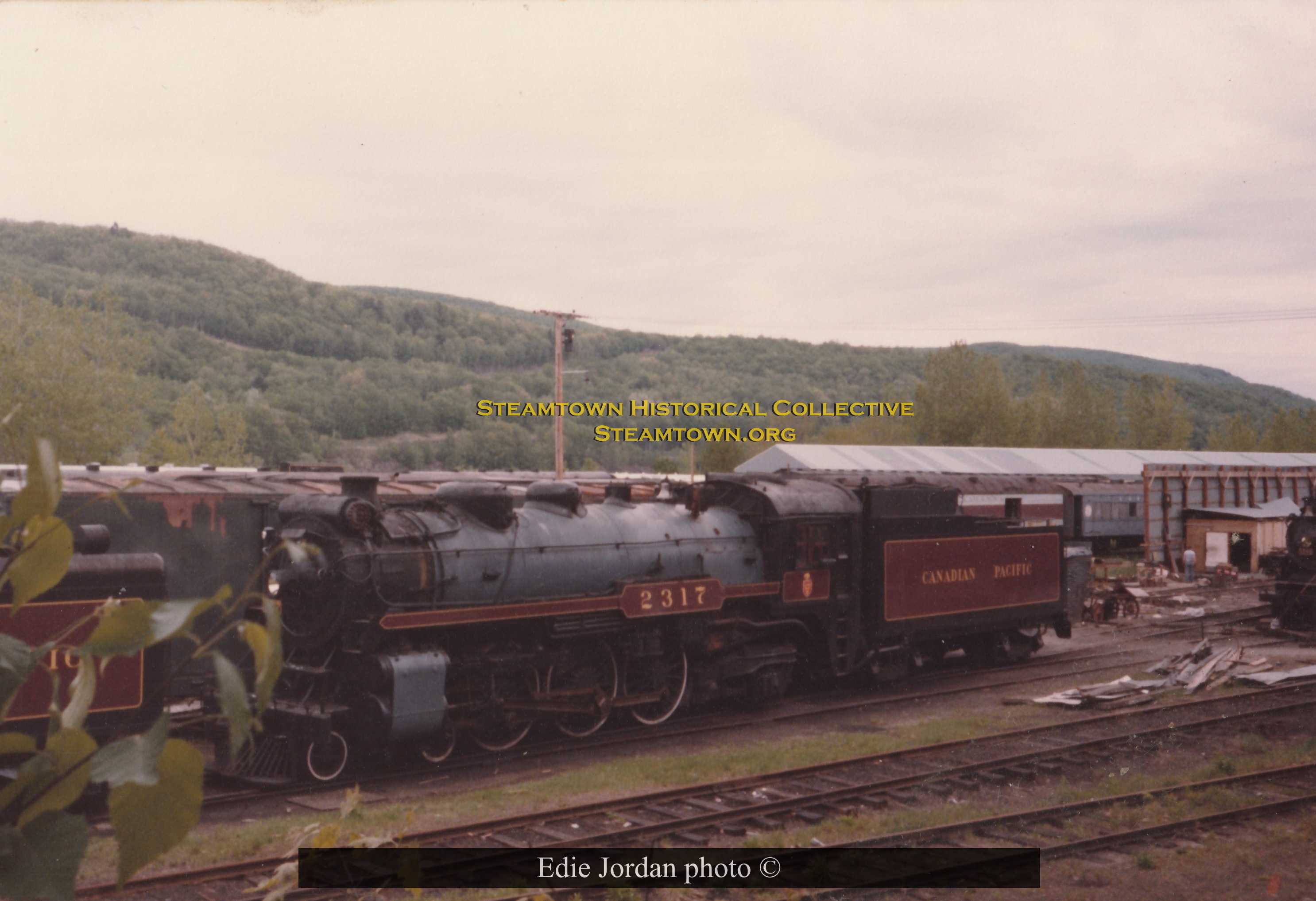

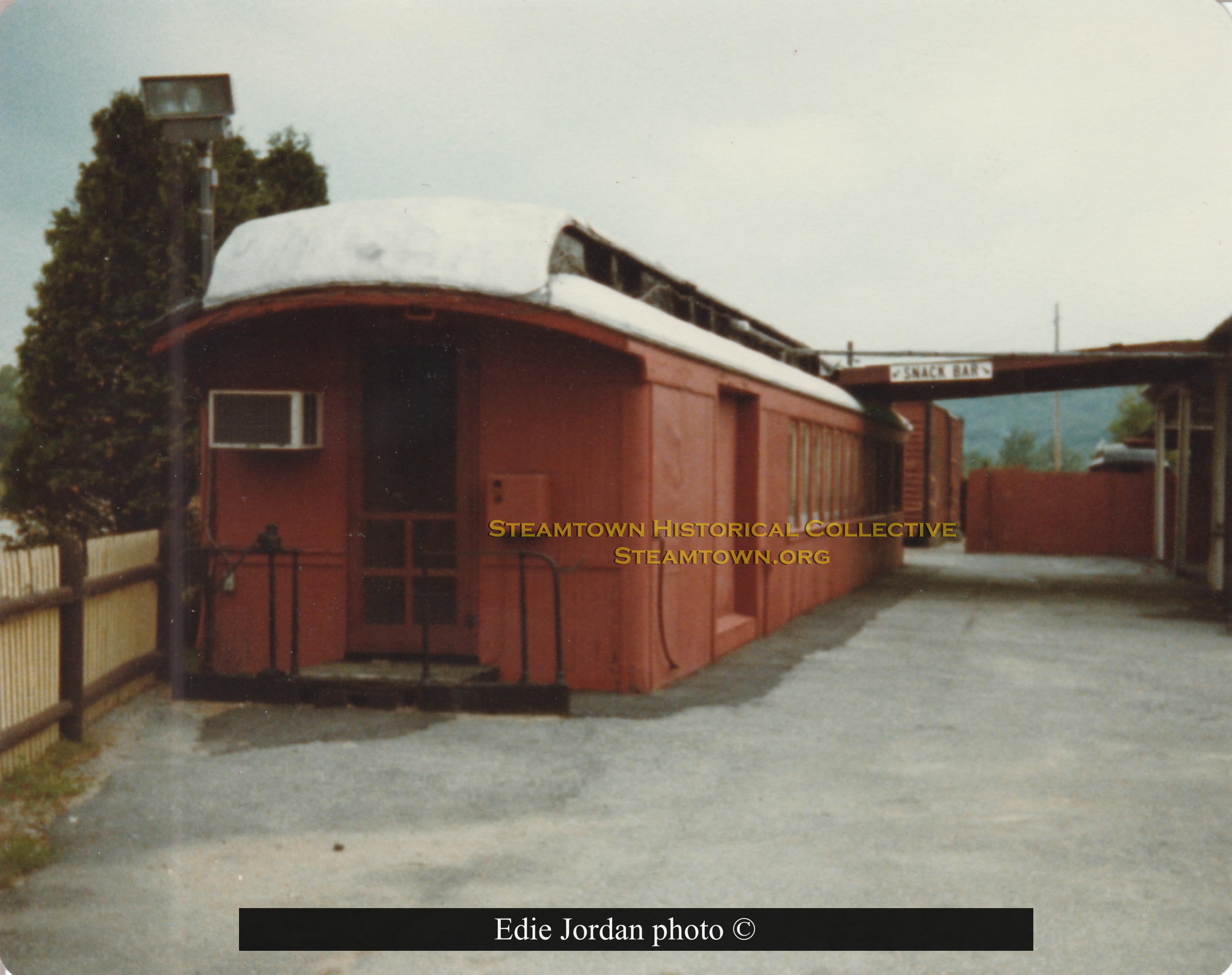

“There were three locomotives in the collection suitable for restoration for Vermont’s Bicentennial train: Canadian National class J-7-b “Pacific”-type 5288, Canadian National class S-1-d “Mikado”-type 3377, and Canadian Pacific class G-3c “Pacific”-type #2317. The state wanted #2317, perhaps the most elegant of the three. Nine former Long Island “Ping Pong” passenger cars were selected for refurbishing and repainting. The official name for the operation was to be the “Vermont Bicentennial Steam Expedition”. It was soon revealed that #2317 would need more extensive work due to pitting and other unexpected problems, so work was expedited on again firing up #1293 after its thirteen-year hiatus. This proved to be less expensive and #1293 was likely better suited to the size and operation of the train. The entire project took major work, as Fred Bailey recalled. “I think one of Steamtown’s greatest accomplishments over the years was putting that train together. We were able to completely refurbish nine cars to the state of Vermont’s specifications. Several of them required major modifications to make a snack bar car and a car to handle bicycles; we had to put electricity in all the cars, outfit a

generator to provide the electricity.

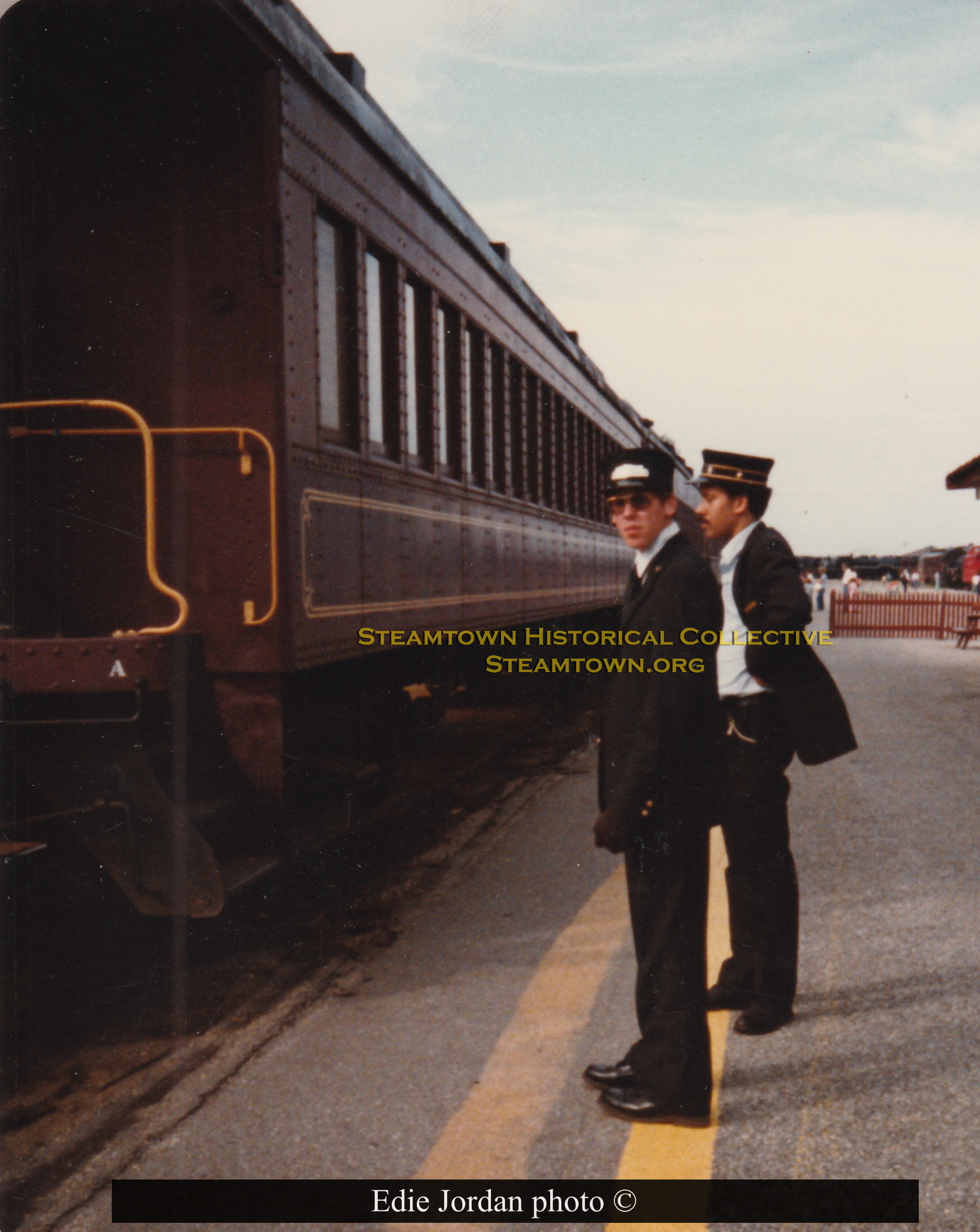

“The train ran six days a week from the first of July up through Labor Day, operated on a schedule that would have been typical of a mainline passenger train in the ‘40s or ‘50s. It was not your typical steam-powered excursion train or tourist railroad. We ran 240 miles a day. Our on-time performance had to be somewhere in the ninety percent range. It was definitely something that Steamtown had to be proud of. It was what I would consider perhaps the last chance that people had in this country to ride a real steam train operated in the way it would have been when steam power was on passenger trains all across the country.”

Unfortunately, despite the mammoth effort and impressive result, the Vermont Bicentennial Steam Expedition was not financially successful. State promotion was not as extensive as it could have been, and negative publicity was directed towards Steamtown, who was perceived as price-gouging the state on operating costs. However, the contract did allow for Steamtown to now have #1293 operational as well as nine additional refurbished passenger coaches; significant work had also been done to #2317 before the priority was changed to #1293, putting the former closer to operation which soon became a reality.

A Farewell to Steamtown in New England

Robert Barbera’s contract was not renewed by the board in 1980. Thereafter followed a brief interim period wherein longtime Steamtown employee Stuart Carter was in charge. Carter had run the gift shop with his wife Irene and had been around during the Blount days. He was able to acquire insurance to allow for volunteer help and his “Volunteer Army” would be essential in helping to reinvigorate the grounds and maintain the museum collection. Carter also ran the foodservice. “His big thing was, give the volunteers a free meal and make them feel that what they’re doing is worthwhile, and you’ll go a long way. It certainly was something that paid off. People would come there and start at the break of dawn and work until sundown,” Fred Bailey remembered. This kindness was reflected in the work of the volunteers, and soon most of the collection was in a far more presentable condition.

Within only a few months Carter’s interim leadership was replaced by Don Ball Jr., a well-known railroad author. His immediate task was attempting to find ways in which to keep Steamtown in Vermont. Unfortunately, that was an uphill battle. The Steamtown Foundation and its many dedicated volunteers had done their best in Vermont but felt that the operation could not survive there. Support from the state and local municipalities had not improved, with directional signage still being denied under the state’s strict guidelines. In many cases, tourists passing through the area continued on without even taking note of Riverside, down along the river obscured by trees. Ball worked with Michael McManus, a syndicated columnist, advertising Steamtown’s plight and desire for a new home. Those in Bellows Falls, reminded of the nationwide offers and hoopla surrounding the museum’s search for a home back in

the 1960s, did not take the news seriously.

However, Ball was reviewing some very significant offers and this time there was no impetus to prioritize Vermont. The final decision was not even certain until Scranton, Pennsylvania, signed a contract to house the museum; it was this commitment that sealed the deal. “I think the fact that they were willing to put the money on the table and sign the dotted line, more than anything else, made Scranton, PA the new home of Steamtown, U.S.A.”, Fred Bailey later testified.

Preparations were made for the move. It was announced after the signing that there would be one final operating season in Vermont, 1983. Hoping to make a positive impression on Scranton, Ball and the board embarked on an advertising campaign for the final season in Vermont. When the season closed, Steamtown had hauled over 60,000 people; it was the best season since the early 1970s. In the last year, passenger operations were provided by a separate entity, the “Vermont Valley Railroad”, in a similar arrangement as the Monadnock, Steamtown & Northern had previously provided for Steamtown, U.S.A. in the 1960s.

Nelson Blount’s legacy drew its final breath in Vermont on October 23, 1983. The Steamtown Foundation and its many dedicated volunteers had done their best in Vermont but felt that the operation could not survive there. Steamtown, U.S.A.’s “Farewell to Vermont” excursions of twenty-two cars departed Riverside for Rutland behind three Green Mountain Alco RS1 diesels and Canadian Pacific 4-6-2 1246. Ultimately, 1,176 people were carried over two trips. Fred Bailey remembered just how well-attended these trips were. “Had we known in advance how popular they were going to be, we could have easily run one more day, perhaps two. We turned away at least one trainload of people.” It seems a cruel twist of irony that the final run of Nelson Blount’s steam-powered legacy in New England was led by diesels, although this was completely necessary to keep their air intakes from being fouled by cinders from #1246.

A positive impression was certainly made; the last trains earned around $70,000 and cost about $10,000 to operate. Fred Bailey, who had started his railroad career as a teenager picking weeds in North Walpole after a chance meeting with his childhood hero F. Nelson Blount in 1963, was incidentally among the last men to work for Nelson’s tourist railroad creation in New England. “The day after the excursions were over, #1246 switched out the yard at Riverside for the last time and lined up the first of the equipment to be sent to Scranton. We backed the locomotive down to the turntable that evening and let the fire burn out, and that was the end of Steamtown operation in the state of Vermont”.

When moving time came, the auctioning and sale of several pieces of Nelson’s original collection commenced. When the auction block closed, forty locomotives and sixty cars were retained by the Foundation and moved over the Boston & Maine and the Delaware & Hudson to Scranton between late 1983 and 1985. Union Pacific “Big Boy” #4012 left town squeezing through the Bellows Falls tunnel on the B&M’s Conn River Line with mere inches to spare. The tunnel floor had been lowered in the years since 1964 when the locomotive was forced to arrive via the Cheshire Branch instead — itself now long abandoned in 1983. All these happenings indicated that chapters were closing at a record pace; not only in Steamtown’s New England history, but in the history of railroading in the region as a whole. In the 1990s the former Steamtown, U.S.A site at Riverside was converted into the Riverside Reload, a busy industrial park and interchange location for the Green Mountain Railroad/Vermont Rail System.

Click the gallery below to view photos and caption information.