A Cavalcade of Steam Power

‘”Dad”, asked my thirteen-year-old son, ‘What is Steamtown really for?’

That’s a penetrating question, I said to myself, and answered aloud ‘Thorn, let me tell you what I think we are doing.’

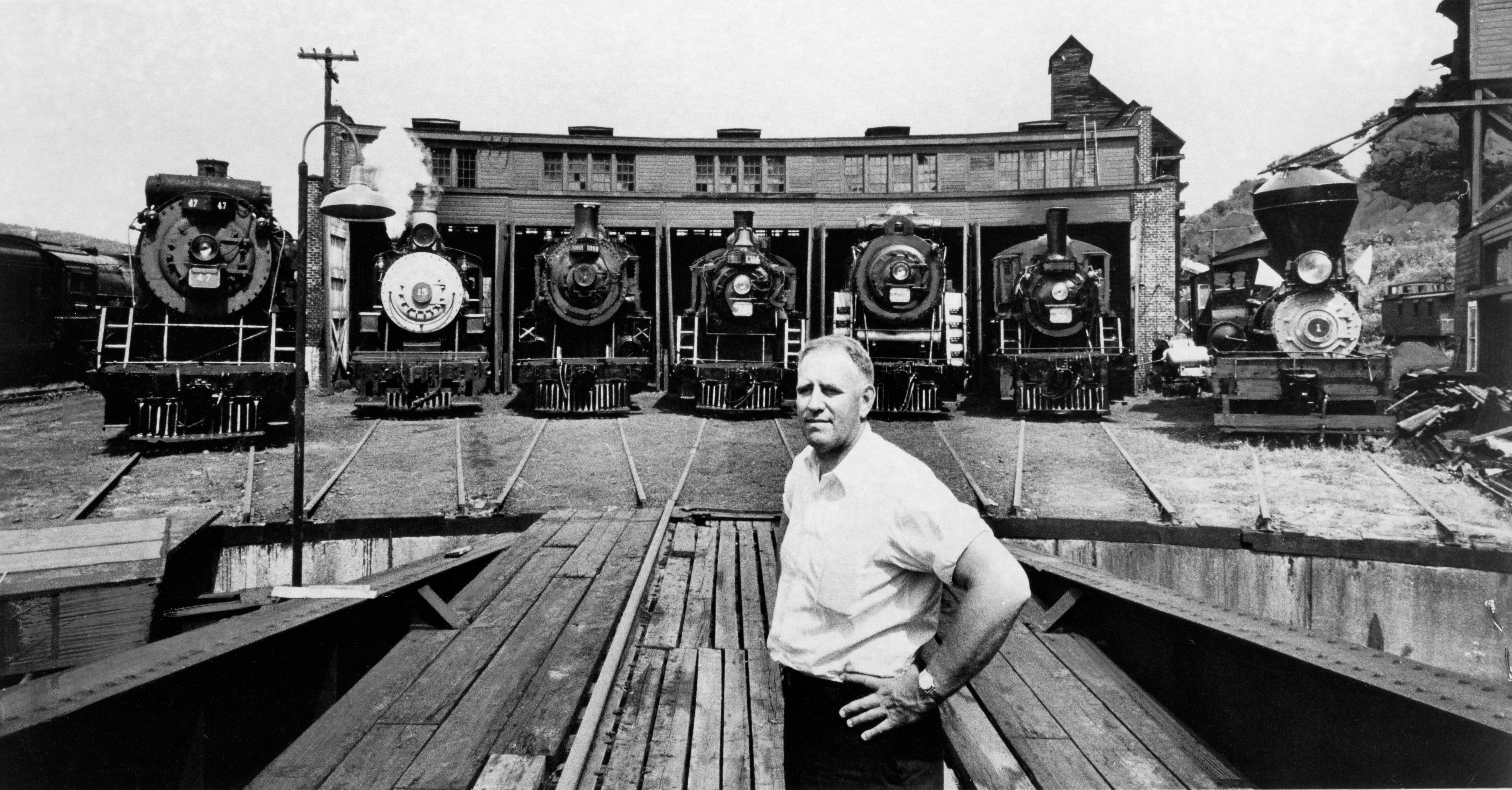

The idea of Steamtown started when a group of steam lovers such as myself, led by Nelson Blount, decided that something must be done to save what remained of the great steam engines which powered our railways and ran our boats and operated our factories. Even in 1959, when the Steamtown idea gained headway the railroads were well on their route to dieselization, and other forms of power were obsoleting the conventional reciprocating form of mechanical motion. We thought that our nation would be well served if a very large collection could be placed at one site, where great multitudes could ride the trains, watch the equipment and learn something in the process.

I felt in my own heart that Blount, the Trustees, and I actually had a very powerful and inspiring message to tell; one which could use any sort of collection, show or display to relate a parable to the public. It was a message that on one hand was very clear, and which the very complexity and vastness of these huge iron monsters of steam could help to make more emphatic.

Blessed with this fine acreage beside the Connecticut River and the beautiful mountains of New Hampshire and Vermont on either side we are further charged with a responsibility to enhance this setting and not let it become a waste land or a commercial bazaar. We have an opportunity to create an attractive, pleasant and natural enhancement to this lovely surrounding countryside.

Nelson Blount and I talked for many hours of the things we would like to have happen at the Riverside site, and while there might be argument on details, there never was question that Steamtown was to be the great monument to steam power.”

– Steamtown Foundation Chairman Edgar T. Mead to the Steamtown Trustees, May 27, 1968.

At the opening of the second half of the twentieth century the steam locomotive had been the dominant symbol of railroading for nearly its entire history. Through its massive contributions to commerce, communication and sociality it had worked its way into the fabric of American culture and everyday life. Songs, writings, and films immortalized the steam locomotive and its smiling, waving engineer clad in denim. Children dreamt of being at the throttle and cherished the wave that seemed to affirm an understanding that they, too, may someday become engineers.

But the days of steam in the United States were mostly dead by 1960 aside from a few holdouts. The introduction of the diesel locomotive, begun in earnest in the 1930s, had paved the way for American railroading’s post-war rush to modernize. Diesels were cheaper to run, easier to clean and maintain, and more economical to operate. For the cash-strapped railroads who had been run into the ground during the Second World War and now faced increasing competition on the road and in the air, the diesel was the key to the future of railroading. By the war’s end, and with transportation hurtling towards a modern age, dieselization became paramount.

With the passing of any era, an effort often emerges to try and pull some of it back out of the abyss, both to educate future generations and to satisfy the nostalgic longings of those not ready to part with what they know and love. As thousands of steam locomotives in the United States and Canada were lined up and scrapped by their respective railroads, enthusiasts in the private sector began to do all they could to prevent a mass extinction event. Some, like Walt Disney and his legendary staff of animators, successfully incorporated their zealous love of steam trains into their enterprises at attractions like Disneyworld. In the Midwest, Richard Jensen purchased steamers from the Chicago, Burlington & Quincy and Grand Trunk Western Railroads, operating them in conjunction with railroad clubs out of Chicago. All across the nation, tourist steam excursion rides and small museums manifested on unwanted stretches of track, offering a dose of nostalgia to the old and new discoveries for the young. The steam locomotive was suddenly in vogue again.

Among these wild and complicated chapters of early American steam preservation is the tale of F. Nelson Blount and his railroad enterprises. Blount is without a doubt one of the most fascinating individuals to ever emerge from the American railroad enthusiast scene. Utilizing his personal wealth he amassed the largest collection of steam locomotives and related artifacts that the country (and very likely the world) had ever seen. He created a steam tourist railroad based in New England, the Monadnock, Steamtown & Northern Amusement Corporation, and fought to create an accompanying museum on a grand scale never before seen — Steamtown, U.S.A., a “Cavalcade of Steam Power” — to educate those doomed to miss that colorful era of railroading. Between 1960 and his tragic, untimely death in 1967, Blount attempted to find a permanent place to operate the MS&N as well as space and support to create his museum at several locations in New Hampshire and Vermont. Eventually that museum, “Steamtown, U.S.A.”, settled in Rockingham, VT, where it remained until 1983 and its famous move to Scranton, Pennsylvania and the eventual creation of Steamtown National Historic Site in 1987.

Steamtown — what it was then, what it became, and what it is today — has a complex history shared by many different people in many different parts of the country. As such, its origins in New Hampshire and Vermont are sometimes condensed, misunderstood, or at worst, forgotten. In fact, “Steamtown”, which did not open as a museum until 1963 at North Walpole, NH, has erroneously become a blanket term to refer to all of Nelson Blount’s early standard-gauge steam tourist operations.

Misconceptions like these are understandable due to the brief and complicated nature of these early tourist operations, which were somewhat fraught with complex political discussion and negotiations. The regrettable result of these misconceptions is that they cloud these colorful early days packed with rich details and absorbing characters not often mentioned within modern discussions of Steamtown. Many individuals involved in those early days, like Attorney Thomas P. Salmon and Anthony Reddington, would go on to hold political office or, like Robert W. Adams, would later preside over other railroads themselves. These were pioneers of the steam preservation and tourist railroad industries; a motley crew making things work, often in the face of challenges both mechanical and human.

These operations provided a final glimpse of steam power in an otherwise dieselized region and afforded photographers an opportunity to capture activity at locations that would otherwise have been neglected and forgotten. For those still living that worked and experienced it, and especially to those who never knew it, the memory of these early operations adds to a shared historical narrative that still generates interest to this day, over a half-century later. With Steamtown’s modern incarnation as a National Park in Scranton, the roots of the collection which make the Park’s existence possible are vital to understanding, and appreciating, its modern existence.

Now, six decades later, the physical connections of this world to that vibrant time have somewhat faded. The main characters — Nelson Blount, Fred Richardson, Governor Hoff, Robert Adams, and so many others — have passed into history after long and illustrious lives. But there are still those among us who made their mark not only on this story, but the historical quilt woven from its many strings. And so the New England roots of a modern-day National Historic Site in Pennsylvania have become partially buried in time, fully visible only at certain times and in certain amounts. But below the ground lies a rich tapestry: this is a story not only of people, places, machines and dreams, but also a rich time period — threads onto which an understanding and appreciation of it all truly begin.

Adapted from Steam Trains of Yesteryear: The Monadnock, Steamtown & Northern Story.

To learn more about specific eras of the Steamtown story, head over to the Media Gallery

Timeline

1918 – May 21: F. Nelson Blount is born in Warren, Rhode Island

1955: Nelson Blount receives his first standard-gauge steam locomotive, Boston & Maine #1455, at Edaville in South Carver, MA

1959-1961: Some of Blount’s equipment displayed at Pleasure Island Amusement Park in Wakefield, MA

1960 – October: F. Nelson Blount acquires the North Walpole engine facility from the Boston & Maine Railroad

1960 – December 12: Planned Steamtown, U.S.A. first announced, initially planned for North Walpole, NH

Late 1960: Blount begins talks with state of New Hampshire to establish Steamtown, U.S.A. museum near Keene

1961 – April 26: Monadnock, Steamtown & Northern Amusement Corporation (DBA Railroad) incorporated to provide excursions for Blount’s planned Steamtown museum

1961 – June 10-11: First moves of Blount equipment from Pleasure Island to North Walpole facility

1961 – July 22: First revenue run of the Monadnock, Steamtown & Northern on the tracks of the Claremont & Concord Railway between Bradford and Sunapee, New Hampshire.

1961 – December: Blount makes first offer to the state of Vermont to purchase the former Rutland Railroad line from Bellows Falls to Ludlow, Vermont

1962 – June 13: Former Rahway Valley 2-8-0 #15 from Blount’s collection is first fired up as Monadnock Northern #15. Re-lettered June 26-28.

1962 – June 28: The state of New Hampshire approves plan for Steamtown, U.S.A. to be created near Keene as a state-funded museum “in principle”

1962 – July 13: Monadnock, Steamtown & Northern makes inaugural run on the Boston & Maine’s Cheshire Branch between Keene and Gilboa (East Westmoreland), NH

1963 – February 16: The state of New Hampshire votes against the creation of a state-funded Steamtown, U.S.A. near Keene

1963 – February: Monadnock, Steamtown & Northern equipment used in the filming of The Cardinal in and around Boston

1963 – March 28: The Steamtown Foundation for the Preservation of Steam and Railroad Americana incorporated

1963 – May 19: First MS&N trip of 1963 on B&M Cheshire Branch (North Walpole, NH – Westmoreland, NH)

1963 – November 13: Articles of Association filed for the Green Mountain Railroad Corporation to handle freight on the former Rutland Railroad Bellows Falls Subdivision

1964 – April 3: Green Mountain Railroad Corporation incorporated

1964 – May 29: First MS&N revenue trip on state of Vermont trackage (Riverside, VT – Chester, VT)

1964 – September 22: State of Vermont purchases Rutland Railroad (Ludlow, VT – Rutland, VT section)

1964 – September 12: Canadian Pacific G5 4-6-2 #1293 placed in service until the end of the 1964 season

1964 – November 1: Last runs of the MS&N’s 1964 season

1965 – January 25: Green Mountain Railroad 2-6-0 #89 (ex-Canadian National) steamed up for the first time since retirement

1965 – March 25: Green Mountain Railroad receives certificate to operate from the Interstate Commerce Commission

1965 – March 29: Purchase agreement reached for former Rutland Railroad ALCo RS-1 #405; assigned to the Green Mountain Railroad

1965 – April 3: Green Mountain Railroad makes first revenue freight run

1965 – May: Engine #127 (CP #1278) purchased by F. Nelson Blount

1965 – May 22: First MS&N excursion of the 1965 season to Chester. VT

1965 – September 23: F. Nelson Blount announces plan to move Steamtown, U.S.A. from North Walpole to Riverside in Bellows Falls (Rockingham, VT)

1967 – April 30: Excursion with 4-6-2 #127 over the New Haven Railroad, Providence. RI to Worcester, MA and return

1967 – May 6: Excursion with 4-6-2 #127 over the New Haven Railroad, Providence, RI to Lowell, MA and return

1967 – May 13: Excursion with 4-6-2 #127 over the New Haven Railroad, Boston, MA – Walpole, MA – Putnam, CT – New London, CT; return to Boston via Providence

1967 – May 13: Excursion with 4-6-2 #127 over the New Haven Railroad, Providence – Attleboro, MA – Yarmouth, MA (Cape Cod) and return

1967 – August 31: F. Nelson Blount is killed in a crash of his private plane off Old Chesham Road in Marlborough, NH, just after 7:00 p.m. He is only 49.

1967 – September 9: Ruth Blount assumes president and CEO status of the Green Mountain Railroad Corporation

1967 – October: Edgar T. Mead named director of Steamtown Foundation

1967 – December 31: Monadnock, Steamtown & Northern Amusement Corporation ceases operations

1968 – January 1: Robert W. Adams assumes title of president and CEO, Green Mountain Railroad Corporation

1968 – June 30 to July 6: Steamtown, U.S.A. sponsored excursions with 4-6-2 #127 over the Boston & Maine’s White Mountain Branch between Laconia, NH and Meredith, NH for Laconia’s 75th anniversary as a city

1970 – August: Passenger operations transferred from Green Mountain Railroad Corporation to Steamtown Foundation

1971 – July 23: MS&N assets transferred to the Steamtown Foundation

1971 – August: Monadnock, Steamtown & Northern Amusement Corporation dissolved

1973: Edgar T. Mead resigns as director of Steamtown Foundation; Robert Barbera assumes the role

1973 – August 11: 2-8-0 #15 suffers a blown boiler tube while leading a triple-header at Riverside. Engineer Andy Barbera is scalded and injured.

1973 – October 27-28: Steamtown Foundation overnight trip from Boston’s North Station over the Boston & Maine through New Hampshire to White River Junction, VT; then over the Central Vermont to Montpelier Junction.

1976: Canadian Pacific G5 4-6-2 #1293 and Long Island Railroad “Ping Pong” coaches refurbished to be used on the Vermont Bicentennial Steam Expedition Train across the state

1983: Last season of Steamtown, U.S.A. in Vermont and New England. Excursions with 4-6-2 #1246 operated under the banner of the “Vermont Valley Railroad”

1983 – October 23: “Farewell to Vermont” excursions operated with 4-6-2 #1246, three Green Mountain Railroad ALCo RS-1s, and 22 coaches.

1984 – 1985: Bulk of Steamtown, U.S.A. collection moved to new location in Scranton, PA at a former Delaware, Lackawanna & Western terminal

1985 – 1987: Last equipment remaining in Vermont sold or scrapped. Riverside eventually converted into a rail freight transload facility.